In the summer of 1967, Dick Proenneke stood at a crossroads that most people only dream of facing. At 51 years old, he had spent decades in the steady rhythm of modern work: a mechanic in California, a carpenter, even a heavy equipment operator on construction sites. But something deeper called to him, a pull toward simplicity and self-reliance that had grown stronger with each passing year. Proenneke had already tasted the wild edges of life, serving in the Navy during World War II and exploring Alaska’s rugged terrain on earlier visits. Now, he decided to quit his job entirely, trading the hum of engines and city bustle for the silence of untouched wilderness. It was not an escape from responsibility, but a deliberate choice to craft a new existence, one log at a time, in a place where survival demanded ingenuity and the land offered no shortcuts.

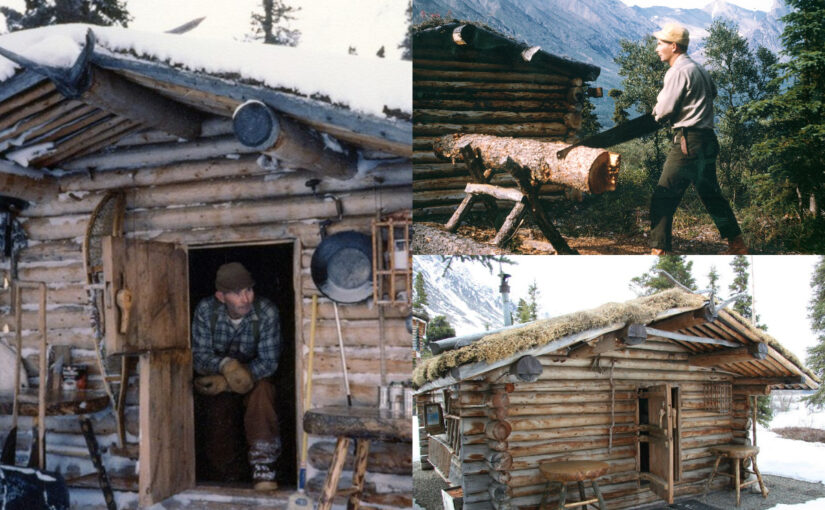

His journey took him to Twin Lakes, a pair of glassy waters nestled in the heart of what would become Lake Clark National Park and Preserve. Accessible only by floatplane or a grueling hike, this remote corner of Alaska stretched out like a living canvas of spruce forests, rolling tundra, and jagged mountains. Proenneke arrived with little more than a backpack, a few basic tools like an axe, a drawknife, and a handsaw, and an unyielding determination. Over the next year, from 1966 to 1967, he felled spruce trees himself, debarking each log with patient strokes until the wood gleamed smooth. He notched the corners with saddle joints, a technique honed from years of carpentry, stacking them into a sturdy 10-by-12-foot cabin that measured just 120 square feet. No power tools marred the process; every element, from the foundation sunk several inches into the earth to the stone fireplace rising along the south wall, emerged from his hands alone. The north wall featured a Dutch door he crafted with intricate wooden joints, a portal between his small world and the vast one beyond. By 1968, the cabin stood complete, a testament to human skill in harmony with nature’s raw materials.

Life inside that cabin unfolded without the comforts most take for granted. No running water meant hauling buckets from the lake or melting snow in winter. Electricity was a distant concept; Proenneke lit his space with oil lamps and cooked over the fireplace or an outdoor stove. His only companions were the grizzlies fishing at the lake’s edge, the moose wandering through the willows, and the eagles soaring overhead. Self-sufficiency became his daily creed. He fished for trout and grayling, their silvery bodies providing sustenance through the short summers. Foraging filled his larder with berries and edible plants, while hunting supplied venison and smaller game. Food storage was a clever underground cache, buried to thwart bears and preserve provisions against the freeze. Chopping wood filled his mornings, each swing of the axe echoing through the crisp air as he built stacks tall enough to outlast the longest nights.

Winters tested him like nothing else. Temperatures plunged below 40 degrees below zero Fahrenheit, turning breath to ice crystals and the lake to a solid sheet. Blizzards howled for days, burying the landscape in drifts that swallowed trails and turned the world monochrome. Proenneke rose before dawn, tending the fire to ward off the chill that seeped through every chink. Summers brought their own demands: the relentless labor of drying fish, gathering firewood, and repairing the cabin against the coming cold. Seasons cycled in a predictable yet unforgiving rhythm, each one a lesson in preparation and adaptation. Yet Proenneke thrived in this cycle, his body toughened by the work and his mind sharpened by the quiet.

What set Proenneke apart was not just his endurance, but his compulsion to record it all. Over three decades, he filled more than 250 diaries with meticulous entries, noting the first crocus of spring or the exact date a bear cub tumbled into the water. He captured these moments on 16mm film too, his steady hand filming the dance of loons on the lake or the slow melt of snow revealing new growth. These were not mere logs of survival; they became a chronicle of nature’s subtle pulses, from the migration of caribou to the whisper of wind through aspen leaves. Proenneke, an accidental documentarian, preserved not only his story but the soul of the wilderness itself, offering future generations a window into a world untouched by human haste.

Imagine stepping into that solitude, where the only clock is the sun’s arc and the only deadline is the weather’s whim. For Proenneke, this isolation bred not loneliness, but a profound purpose. He found harmony in the land’s demands, each task a meditation on living intentionally. Chopping wood was more than labor; it was a rhythm syncing his heartbeat with the forest’s breath. Fishing became a quiet communion with the water’s depths. In this hand-built life, he discovered a balance that modern existence often eludes: the joy of creating what you need, the peace of depending on no one but yourself and the earth.

His iconic cabin embodied this philosophy. Those debarked spruce logs, fitted with saddle-notched corners, spoke of precision amid chaos. The handmade Dutch door, with its dovetailed joints, swung open to invite the wild inside, while the stone fireplace warmed not just the body but the spirit of the place. It stood as an enduring example of wilderness homesteading, proving that beauty and function could arise from simplicity.

Proenneke remained at Twin Lakes until 1998, when at 82 years old, health concerns drew him back to civilization. He left behind a legacy etched in wood and words: a portrait of independence that challenges the soul. His story whispers of resilience, of choosing depth over distraction in an age of excess. It reminds us that true freedom lies in shedding the unnecessary, in tuning our lives to the wild’s honest cadence.

Today, Proenneke’s cabin endures within Lake Clark National Park and Preserve, one of the best-preserved handmade homesteads in America. Visitors who make the trek find not just a structure, but an invitation to reflect on slower living. In a world accelerating toward disconnection, his tale inspires those yearning for simplicity, urging them toward nature’s embrace and the quiet strength of solitude. Proenneke did not conquer the wild; he became part of it, showing us all that such a life is possible, if only we dare to build it.

Header images: Richard Proenneke, donated to National Park Service.

Feeling the call of the wild? Or just vibing with unconventional ideas? If so, let yourself go a little. Toss a tip in our virtual jar and help keep the blog fresh, fiercely independent, and full of wisdom worth sharing. Click below to keep the stories and the wild thinking going strong.